Publication | Growing Successful Community Gardens

Publication | Growing Successful Community Gardens

INTRODUCTION

How do we make community gardens more successful and help them persist through time with less reliance on Extension? This publication identifies five criteria that are important for the long-term success of a community garden:

(1) land security; (2) community support; (3) resource mobilization; (4) environmental conditions and garden design; and (5) governance, management, and leadership.

The article then spotlights the special significance of governance structures, digging deeply into our fifth criteria. Governance has to do with decision-making and who leads the community garden. Original research conducted by Amanda Beavin (Honors student at Western Kentucky University), in collaboration with University of Kentucky Extension (Horticulture Agent, Bethany Pratt, & Community Development faculty member, Nicole Breazeale), finds that gardens with more grassroots control are more successful. We describe three things that Extension can do to build capacity and strengthen the self-governance of community gardens. First, Agents can invest in leadership development of garden residents. Second, Agents can foster community building amongst gardeners. Finally, Agents can diversify and strengthen partnerships with external organizations and community members. We provide concrete suggestions and examples on how to do this.

The value of this publication is to lift up under-appreciated aspects of community garden success—especially the critical importance of investing in relationship-building and transferring control to gardeners. This publication might also be used by Extension Agents to help identify new criteria to evaluate and discuss in success stories, beyond the traditional measure of pounds of produce. For example, Agents might consider asking: How many garden leaders are there? Are there frequent get-togethers? How many folks are volunteering, spending significant time and resources to make the garden thrive? How many community partners are involved? Is the land secure? As described below, these are all indicators of well-functioning and “successful” community garden. This publication can be used in combination with the Louisville Department of Economic Growth & Development’s (n.d.) “Community Gardens in Louisville: A Start-Up Guide” and UK Cooperative Extension’s (n.d.) “Community Garden and Horticulture Therapy Sample Evaluation” tool.

Key criteria of community garden “success”

What is meant by garden “success” and how would you measure it? Through a review of the literature on community gardens, we identified five key elements that help a garden survive in the face of challenges. Gardens can be assessed along each of these indicators; those that score high are considered “successful.” Note that most community gardens are continuously working to strengthen one or more of these key elements.

- Land security: Access to land with a long-term agreement is the most important factor for building a successful garden. If a community can secure a long-term site, the security enables larger investments in infrastructure, garden design, and community building.

- Community support: Strong support and engagement within a garden (including garden participants, leaders, and surrounding neighbors) can increase access to funding, land opportunities, resources, volunteers, and technical knowledge. Furthermore, local awareness enables effective recruitment of new gardeners and increased long-term participation. Partnering with a variety of local institutions, such as neighborhood associations, churches, community centers, and local government officials is a great way to increase community support.

- Resource mobilization: Most community gardens access funding and resources through personal networks. Diversity in garden participants, along with multiple institutional partnerships, can increase the available pool of resources, ensuring the garden can meet its long-term financial needs. In the case of gardens that are attached to specific institutions, it is also helpful to have several different individuals involved in mobilizing resources together.

- Environmental conditions and garden design: A garden designed to the specific goals and needs of its users is most successful in the long run. In addition, quality soil, sunlight, regular water access, and a gathering space are enablers of sustainable community gardens.

- Governance, management, and leadership: Governance issues and leadership development are also critical components of a successful garden because they provide the framework for how a community garden functions. This aspect of community garden success is the least studied and most under-appreciated, thus it served as the main focus for our original research.

For those who want to learn more about practices to improve success in the first four areas, see the Louisville Department of Economic Growth & Development (n.d.) guide, created with support from Jefferson County Cooperative Extension Service.

Defining community garden “governance structures”

Governance and management both refer to how decisions are made and how resources are allocated. Governance has more to do with setting the overall direction and framework for the garden and management has more to do with overseeing the running of the garden. Community garden governance can fall along a spectrum from top-down (the community garden is initiated by an institution, which sets all the rules and makes all the decisions) to bottom-up (the community garden is initiated by a group of residents who work together to run the garden, make decisions, and allocate resources). The most common structure seen in gardens, especially gardens with Extension involvement, is a hybrid or shared model where an institution provides technical, infrastructural, and financial resources while the community handles the day-to-day decision-making and development.

Regardless of the type of governance structure, leaders are key actors in the garden’s success. Garden leaders, who are often the main connection between Extension and the broader garden community, serve many roles. They can help encourage participation, use networks to acquire resources, and direct the garden’s development in the interests of the gardeners and broader community. Within the decision-making structure, garden leaders are often at the center, collecting ideas and thoughts from participants and organizing community conversations. What does research tell us about the best way to set up the governance of a community garden and how to train effective garden leaders?

Beavin’s study: Governance structures and their impact on garden success

To better understand the relationship between garden governance structures and garden success, Amanda Beavin (2021) studied three garden sites in Louisville, Kentucky. All three gardens had a hybrid governance structure where an outside entity provided some assistance, but they varied in terms of how much help they required. In other words, some gardens were far more ‘self-governed’ than others. Beavin then rated each community garden according to key indicators of success. She found a strong relationship between self-governance and garden success. In other words, gardens that functioned more independently had higher levels of overall “success.” In real terms, this meant they were able to successfully weather challenges to their land security and keep gardeners coming back year after year.

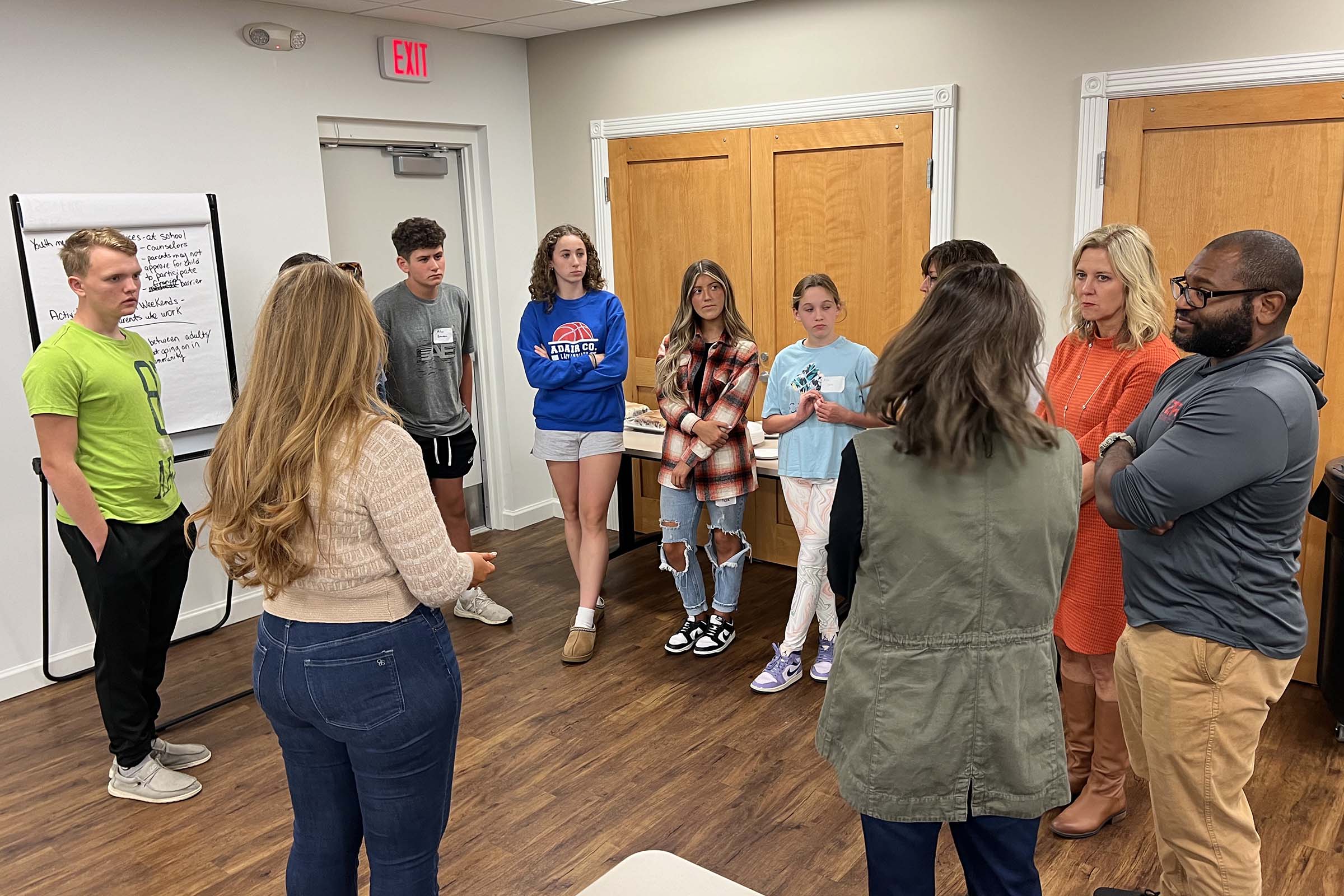

Why was this, and how did they make this happen? In Beavin’s study, three characteristics seemed particularly important: frequent community engagement, strong social cohesion, and a “people-centered” leadership style. The gardens with strong self-governance invested deeply in building community, both within and outside of the garden. Two gardens in the study had regular events that brought all the participants to the garden space at one time, such as annual garden meetings or summer potlucks. These events helped develop social relationships and trust among the gardeners, which strengthened their willingness to work together and make collective decisions. Other activities that aided in developing social cohesion included regular opportunities for volunteer activities and neighborhood engagement. For example, one community garden worked hard to communicate regularly with their neighborhood association and area churches, which built strong bonds of mutual trust. When issues arose (specifically a threat to their land), they were in a good position to solve the problem themselves, drawing on support from the neighborhood association and city council member when they went into conversations with the prospective land buyer. Importantly, they were successful in their actions and the garden has continued.

Leadership style and abilities are also important for enhancing self-governance. Beavin found that community gardens with more self-sufficiency had garden leaders who invested in relationship-building. These leaders had a “people-centered” approach to community gardening, frequently communicating with gardeners and other stakeholders about weed notices or garden news and planning social events and garden meetings. This leadership style increased the leader’s knowledge of what the garden community wanted and enabled them to organize gardeners more effectively around these matters. Building strong relationships within and outside the garden are key to developing long-term self-governance.

Suggestions for how to improve the self-governance of community gardens

What can Extension Agents learn from this research? Given that self-governance is strongly linked to garden success, Agents can invest in building the capacity of gardeners and partner institutions to share decision-making power and take on additional problem-solving, management, and community building responsibilities. What skills are particularly important for Extension Agents to teach?

- Invest in leadership development of garden residents: Garden leaders are key actors in the long-term sustainability of a community project! Above all, regular communication with garden participants, conflict management, and trust-building are critical skills for garden leaders to learn. Extension Agents can focus on developing leaders through an annual leadership training or through long-term, informal skill-building of garden leaders (e.g., weekly conversations focused on developing specific skills). Appropriate support and training will contribute to building confident, competent leaders who can guide their communities through collective decision-making. At the same time, Extension can also train garden leaders in research-based best practices of garden management, such as remedies for pest control, which further increases their capacity.

- Foster community building amongst garden participants: Building a shared vision or shared set of values within the garden community is an important step towards encouraging shared decision-making. Incorporating time for garden participants to interact and discuss the garden through regular social events or garden meetings allows the community to grow. Extension can encourage community building by helping to host annual or quarterly garden meetings or social events, such as a potluck or barbecue. Anything that brings together the participants in one space is helpful.

- Diversify and strengthen partnerships with external organizations and community members: Relationship-building beyond the garden participants is essential to building self-governed, successful gardens. External partnerships with local non-profits, churches, schools, libraries, neighborhood associations, and other groups increases the pool of resources and support for a garden project. Strong relationships with community members and institutions provides an expanded network that garden leaders can draw on when mobilizing resources for the garden space or encountering a crisis, like a land threat. In order to encourage this type of network-building, Extension could help plan events, such as an annual neighborhood clean-up in collaboration with the neighborhood association or local community group. These types of events develop relationships of trust between the neighbors and garden participants, thus widening social support for the community garden.

CONCLUSION

Given limited resources, Extension Agents who provide support for community gardens to create their own leadership structure can learn from this research and increase the capacity of such gardens to be self-governed. Not only does this reduce long-term reliance on Extension Agents to manage such collaborations, but the up-front investment increases the chance of the garden’s success. Empowering garden residents to be effective leaders is an important first step. Investing in community building activities and helping to foster strong relationships with a variety of external partners and neighbors are other important strategies for achieving this goal.

REFERENCES

Beavin, A. (2021). Pathways to self-governance and success: An exploratory study of community gardens in Louisville, Kentucky. [Unpublished Bachelor’s thesis]. Western Kentucky University.

Drake, L., & Lawson, L. J. (2015). Results of a US and Canada community garden survey: Shared challenges in garden management amid diverse geographical and organizational contexts. Agriculture and Human Values, 32(2), 241-254.

Fox-Kamper, R., Wesener, A., Munderlein, D., Sondermann, M., McWilliam, W., & Kirk, N. (2018). Urban community gardens: An evaluation of governance approaches and related enablers and barriers at different development stages. Landscape and Urban Planning, 170, 59-68.

Gilbert, J., Chauvenet, C., Sheppard, B., & De Marco, M. (2020). “Don’t just come for yourself”: Understanding leadership approaches and volunteer engagement in community gardens. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(4), 259-273.

Louisville Department of Economic Growth and Innovation. (n.d.). Community gardens in Louisville: A start-up guide. http://online.fliphtml5.com/kkdk/bzmg/#p=1

Milburn, L.S., & Vail, B.A. (2010). Sowing the seeds of success: Cultivating a future for community gardens. Landscape Journal, 29, 1-10. University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension. (n.d.). Community garden and horticulture therapy sample evaluation. https://anr.ca.uky.edu/files/sample_community_garden_evaluation.pdf